Yes, we do know social media isn't safe for kids

What the Washington Post editorial board got wrong about the research

It’s been quite a year for news on teen mental health and technology use. In March, the CDC announced that 30% of American teen girls considered attempting suicide in 2021, up from 19% in 2011 — and persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness had also increased among both girls and boys. Then in May, the Surgeon General’s office released a report on social media and youth mental health. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy said, “The most common question parents ask me is, ‘is social media safe for my kids’. The answer is that we don't have enough evidence to say it's safe, and in fact, there is growing evidence that social media use is associated with harm to young people’s mental health.”

Dr. Murthy based that conclusion on a review of the research in the area. Two points are especially relevant. First, teen depression began to rise in the early 2010s, right as smartphones and social media became ubiquitous (Jon Haidt and I maintain a public Google doc with all of this research here). Second, the more hours a day a teen spends on social media, the more likely he or she will be depressed — and there is growing evidence that social media use causes depression, not just that it’s correlated (that Google doc is here).

This week, the Washington Post editorial board responded to the Surgeon General’s report with the well-worn (and now false) trope that “we don’t know enough yet.” Even more unfortunate, they came to this conclusion using arguments that have been refuted for years, which even a cursory read of the research would have instantly proven wrong. The board acknowledges that there is no question teen depression has risen in the age of the smartphone (which, at least, is progress). But then they say:

— “… there are questions about whether the spike in social media use is responsible for the increases in depression and suicide. There are other possible causes, such as economic anxiety or the opioid crisis.”

No, there’s not — at least not these. Let’s take these one by one. If the cause were economic anxiety, why wouldn’t depression have increased during the Great Recession 2007-09? And why would the increases be the largest among the youngest adolescents, who are the most removed from the job market? For example, here is the CDC data on self-harm among girls, which nearly doubled among older teens but quadrupled among 10- to 14-year-olds:

Figure 1: Rates of emergency room admissions for self-harm (non-suicidal self-injury) among U.S. girls and young women, by age group. Source: CDC See also: Generations, Gen Z chapter

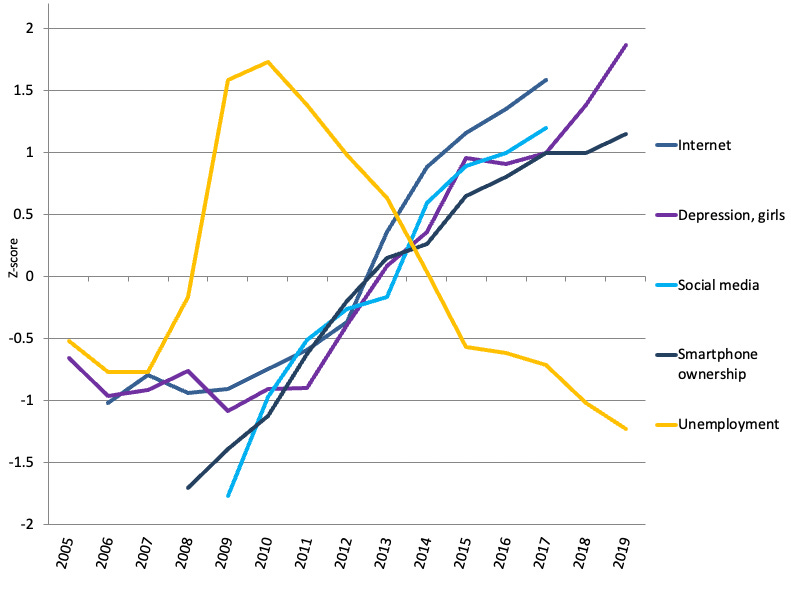

Self-harm was stable or down during the years of the Great Recession, and then started to increase after 2010, just as the U.S. economy began to improve. In fact, economic indicators are exactly misaligned — unemployment declined as teen depression and self-harm rose (see Figure 2). We’ve known this for nearly six years; there was a similar chart in iGen, first published in 2017.

Figure 2: U.S. teen girls; depression rates and possible causes, 2005-2019. Sources: Monitoring the Future, National Study of Drug Use and Health, Pew Research Center, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics See also: Generations, Gen Z chapter

Next, the opioid crisis. The increase in opioid deaths is primarily among middle-aged people, not teens (the page also notes “Few opioid deaths occur among children younger than 15” — yet that’s the group with the largest increases in depression and self-harm). Opioid deaths are also very regional (see Figure 3), with large increases in some areas of the country and little in others. In contrast, the increase in teen depression was nationwide.

Figure 3: Opioid overdose deaths, West Virginia vs. California, 1999-2021. Source: Kaiser Family Foundation data analyzer

Although the Post didn’t mention it, another common argument is that the increase in teen depression is due to school shootings. If that were true, we would expect to see no changes to teen depression and loneliness in places outside the U.S. that do not experience school shootings at the horrific rate that we do. Instead, adolescent loneliness and depression spiked worldwide.

Also: Social media and smartphones fundamentally changed the way teens use their time outside of school. They had the biggest impact on the day-to-day lives of the most teens. No other cause even comes close. This is the question for critics: If it wasn’t technology, what was it? In six years, no one has been able to answer that question.

The Post then says:

— “A decrease in stigma around mental health conditions could also explain some of the surge: Kids were always depressed; they just weren’t always talking about it — though a rise in mental health-related emergency room visits suggests this is not the whole story.” The rise in mental-health related emergency room visits actually suggests this is not the story at all. These are objectively measured behaviors not subject to self-report bias, and the increases are just as big or even bigger than in self-reports of symptoms. Suicide rates are also (obviously) not subject to self-report bias, and they have also increased, doubling or tripling among teens since 2010. A decrease in stigma — if there even is one — can’t explain the increases in self-harm and suicide. It’s strange that the Board brings this up and then immediately refutes it. Why waste the ink?

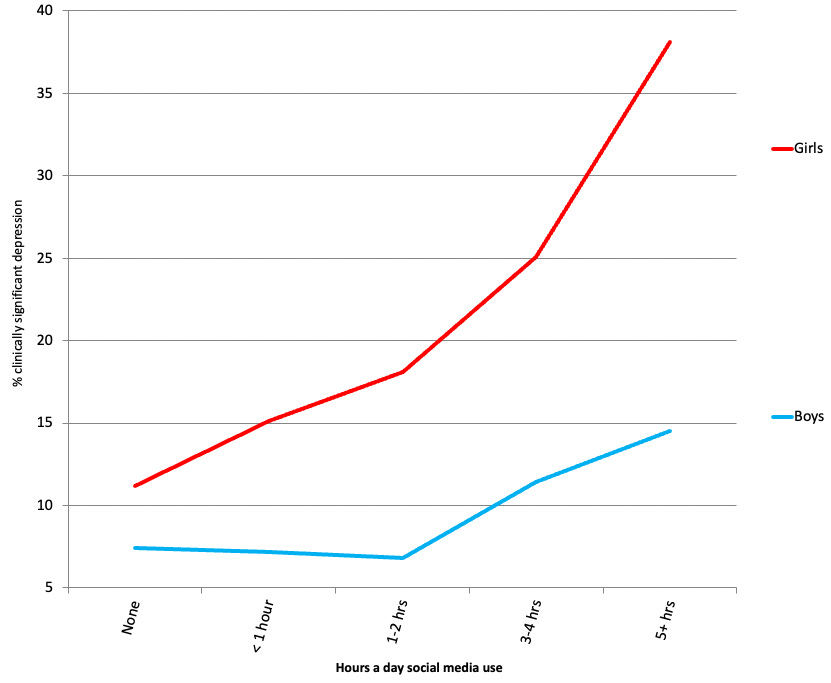

— “Statistically, some studies have found significant associations between heavy social media use and mental health challenges; others, including an analysis focused on the more general category of ‘digital technology,’ have found that the correlation of mental health issues to spending a lot of time online is only as strong as the association between mental health problems and benign activities such as “eating potatoes.” The “potatoes” study, which included watching TV and owning a computer as “digital technology,” has been thoroughly debunked for awhile. Two researchers from Spain concluded that the potato authors’ statistical analyses were “severely misleading,” obscuring large and meaningful links between technology use and depression. Other researchers looking at the same data and focusing specifically on social media came to the same conclusion: Heavy users of social media were twice as likely to be depressed as light users — three times as likely among girls (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Hours a day spent on social media and clinically significant depressive symptoms, U.K. teens. Source: Kelly et al. (2019)

— “There’s also the possibility that what’s most harmful for the average kid isn’t social media use itself, but rather how it swallows up hours that would otherwise be devoted to the activities that science shows very clearly are beneficial for mental health, such as exercise or, crucially, sleep.” Exactly! Time displacement isn’t the only problem with social media, but it’s up there. It’s unclear why this is presented as contradictory evidence for the harm of social media.

— “The vast majority of the meaningful associations researchers have found, in any case, are merely correlational. Causal relationships have been difficult to discern …” No, they haven’t: There have been many experiments on social media use and depression, and most show that less social media use causes mental health benefits. As just one example, people paid to give up Facebook for a month (vs. those who kept up their use) ended the time in better mental health (see Figure 6). Saying that the vast majority of the studies in the area are correlational is irrelevant — that’s because those studies are easier to do. That doesn’t undermine the existence of experimental studies that show effects.

Figure 5: Giving up Facebook and mental well-being. Source: Allcott et al. (2020)

— The Post concludes, “Yet so far, the country also lacks the evidence to conclude whether and how it is hurting them. For now, the best treatment plan is to get those answers …” We have the evidence and the answers now. How much longer are we going to wait when rates of self-harm have quadrupled among 10- to 14-year-old girls?

There’s also the risk-benefit equation. What is the risk in restricting social media among those (say) 15 and under? Pretty low. What is the risk in doing nothing as more kids become depressed and harm themselves? Very high.

The time to call for “more research” was 10 years ago. We now have the research. Now we need action — not more more dithering.