(Editors Note: Rare is the person who stops to think about how online “search” works, or how search algorithms reinforce beliefs, for good or ill, all while convincing us we’ve “done our research.” Inscrutable algorithms power search—and are now being embedded in the AI that will shape our future, whether we want it to or not. We’re re-releasing this 2016 article as the central points are as relevant in 2024 as ever.)

For the first time in history, we can seek instant answers to any questions we may have. But how long before search engines start defining the questions themselves?

If you open the Google search app on your phone right now, you’ll be welcomed by a very bold question: “Want answers before you ask?”

Of course, this is part of the company’s captivating branding, but when I read it for the first time, it sounded rather eerie. The moment an algorithm wants to give me unprompted answers, isn’t it also deciding the questions without my input?

“We must consider that there’s a limit to what we can input in the first place,” says Anthony F. Beavers, professor of philosophy at the University of Evansville in Indiana. “Yes-or-no questions, say ‘Is Nelson Mandela dead?’ are immediately ascertainable, but what about more nuanced questions like ‘What does this mean for the country?’ Obviously, that’s much harder to ask of Google alone.

“We must distinguish between online information, which we can find on the Internet, and onboard information that we carry along with us. To look for the former, I need the latter—a rough idea of the answers I’m seeking. Online knowledge alone doesn’t get you very far.” As Bertolt Brecht put it in Life of Galileo, to look in the glass one must know there is something to look at.

Regarding whether or not search engines are doing us the “favor” of deciding the questions themselves, Beaver’s answer comes off as surprising: “We’re pretty much past that point already. Search engines use past behavior to hone future searches, so that the results to my liking are more likely to pull up at the beginning. On the other hand, results disproving my beliefs might only come up on page seven or eight, which I’ll hardly ever get to.”

He adds that we live in an age of “whispers”: the information comes all at once, without the time to vet it properly. Yet instead of visualizing it into chaos, Google displays it linearly. “Search engines may not define the truth, but they sure define relevance. They create an image of what matters for us.”

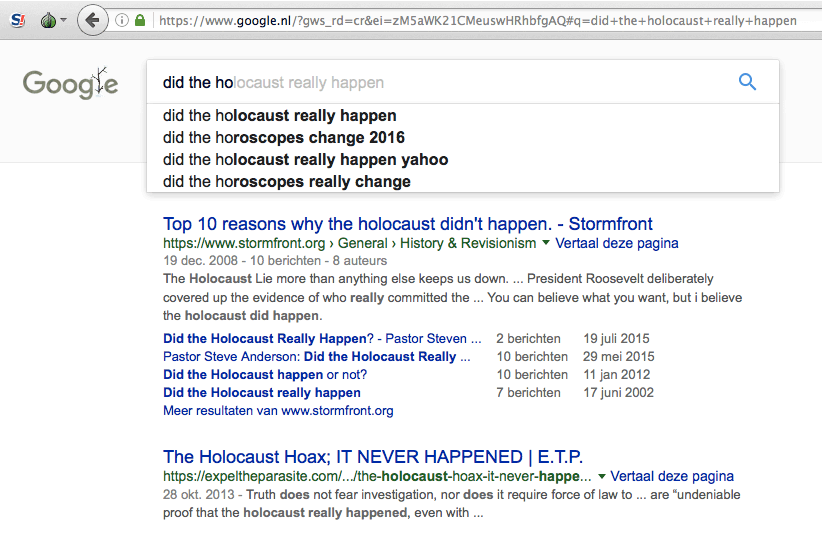

Nothing demonstrates this more chillingly than reporting earlier this month by the Guardian showing that Google’s top result in a search about the Holocaust in many countries was a white-nationalist website denying that it happened.

Screen shot of a December 21, 2016 Google search via The Netherlands. A boxed announcement in Dutch was removed for space and clarity.

Luciano Floridi, of the Oxford Internet Institute, points out that search engines are competitive enterprises that will attract users in any way they can. He compares this to supermarkets’ sale strategies: “The basic principle is, the more people ask of something, the more you give it to them. You don’t bother to interest them in other items on the shelf.” In supermarkets and on search engines alike, then, we’re offered items before even asking for them.

Floridi thinks the Internet unmasked humans’ true tendencies: “Until a few decades ago, we had excuses, so to say: information was not readily available, or accessible. But when we literally have the Internet in our hands, and still don’t use it to fact-check, our nature is unveiled: it’s not that we don’t have access to knowledge, it’s that we don’t want to review our beliefs.” He connects this to our basic instincts as animals: run first, ponder later.

iStock.com / Gaju

The issue, of course, is not just about search engines, which are query-based. Other big web giants like Facebook and Twitter, are feeds: by design, they provide links without being asked. And once again, it only provides what we’re likely to approve of.

“A Facebook conversation rarely gets as long as a live one. On top of that, it’s missing all the body language and the nuances that we get face-to-face. The discussion gets progressively polarized between my position and the one against.

“It’s a problem of confirmation bias: there’s too many voices coming, so I end up listening to those closer to my thinking. I can be led to believe that my position—and that of my Facebook friends—is representative of the wider population, when in fact it’s just a minority. But it’s basic human behavior to reduce complexity, one that predates the Internet. [The algorithm] simply capitalizes on it.”

It may sound like the Internet—crystallized in its big symbols—is on trial here, but Beavers is not too soft on traditional media outlets either. He thinks fake news would be much easier to spot if actual news wasn’t designed the way it is: “What would have been a single, long news story ten or fifteen years ago is now broken down in five or six different headlines, which generate as many Google links. But of course, you can’t include the fact-checking in the headline. And most of the time, that’s the only thing people read.”

Floridi connects the current state of things with how the Internet dawned. He makes an analysis that would make Foucault—who believed that “there is no knowledge without power”—proud: “Policy-makers mistakenly believed that it would be state actors who would take the reins of the World Wide Web. Instead, it was the big private corporations: IBM, Microsoft, Google, Facebook. So far, we were lucky that commercial interests didn’t collide with the free spread of knowledge. But how long can it last?”

So how do we escape a future in which the Internet becomes an information wasteland— where innuendos and falsehoods resonate just as loud as truths—rather than a repository of shared, accountable knowledge?

“I’m not too optimistic about the user base,” says Floridi. “The divide will grow between those who use online tools critically and those who are ‘used’ by them. Usually, it’s personal temperamental dispositions that Google merely reinforces.”

“Nevertheless, education can—and should—do its part. Once all the information is up there, there needs to be a shift towards softer, critical thinking skills. We need to teach and learn the different languages of knowledge: not just spoken languages, but also mathematics, music, philosophy. Otherwise, I’ll be presented with loads of information without being able to assess it.”

I asked Floridi who will be tasked with this radical shift: millennials, maybe, or “Generation Z.” He says he doesn’t know for sure. However, he does give an ominous warning: history teaches us that we only make changes after catastrophes.

Whether 2016 qualifies as catastrophic is for us, not Google, to determine. But it did leave us with one certainty: the Internet is still a big, uncharted territory.